28 Jan 2021

Resilience: It’s not a fad

Resilience seems to be having a day in the sun, but don’t be deceived – it is a concept with deep roots and, used effectively, can create powerful change. RMCG Principals Claire Flanagan-Smith and Shayne Annett explain more.

Resilience – growing in use

The concept of resilience has become widely adopted over recent years. It is being used by a broad spectrum of public and private sector organisations to shape strategy and action. Many development agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have adopted resilience building as a core approach, investing heavily in on-ground resilience focused actions. Over the last year in particular, it has seemed that the term is suddenly everywhere.

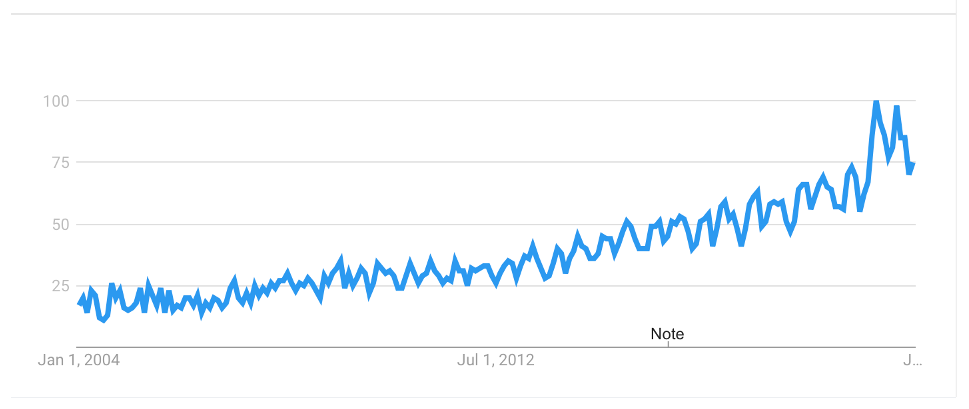

Google trend data shows that relative interest in the term “resilience” has indeed increased over time, but the rise has been steady rather than sudden, albeit with an extra leap in early 2020. Figure 1 suggests that interest in resilience was highest in April 2020 – right about the time that Victoria went into its first lockdown.

Figure 1: Relative worldwide search interest over time for the term “resilience” from January 2004-January 2020. Source: https://trends.google.com

Note: Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term.

In defence of “resilience”

As government and business have begun to adopt resilience language, there has been a corresponding rise in cynicism that it is just the latest buzzword. But to dismiss resilience in this way is to dismiss a deeply useful concept that can be used to help people, organisations, infrastructure and landscapes manage with change in positive and enduring ways.

While we sympathise with the frustration caused by misuse and hype around the term, throwing out the term altogether isn’t the answer. The job is to bring people to a deeper understanding of resilience. This kind of change takes time.

Anyone working or studying in the environmental field in the early 2000’s might remember some torturous discussions and written arguments attempting to define sustainability, followed by another decade or so of people dismissing it as a buzzword. But it is an example of a concept that has persisted and has led to great achievements when people applied its inherent ideas rather than debating the word itself.

Resilience, like sustainability, has deep theoretical roots and a strong evidence base. We need to get on with applying its concepts, rather than being distracted by arguing over definitions or trying to find another (im)perfect term.

So what do we mean by resilience?

The term resilience is used across a range of fields, from mathematics to the social sciences. Each field has its own nuanced interpretation of resilience, however all have some element of coping with, or responding to, stress and change in positive ways.

Resilience concepts are rooted in systems theory – the idea that things like regions, landscapes and communities are complex adaptive systems rather than simple systems with simple answers to their challenges. In complex adaptive systems, there are many interconnected and unpredictable relationships; there are interactions and feedback loops between the people, organisations, environments, infrastructure and laws. Because of this complexity, they (regions, landscapes and communities) cannot be controlled by working with just one part of that system. Further, attribution of cause and effect in complex systems is very difficult.

“We can’t impose our will on a system. We can listen to what the system tells us and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone.” ~ Donella H. Meadows.

RMCG has used this understanding in our work and further developed our understanding of resilience by working with Paul Ryan from the Australian Resilience Centre. Together, we use resilience as a framework to help people to identify and understand how, for instance, a community (a complex system) can respond to change in positive ways.

Resilience isn’t necessarily good or bad. Some very undesirable things (such as intergenerational poverty) are very resilient. The key is to be clear about what things we want to be resilient (environmental assets, human health, democracy); which things we don’t (pollution, poverty, inequality); and use resilience principles to work out how to intervene in the system to build the former and erode the latter.

An example of resilience concepts in action can be seen in the recently launched Goulburn Murray Resilience Strategy. RMCG assisted in the preparation of this strategy, which had a particular focus on how the region could meet the challenges that will come with a future where less water is available due to changes in water policy and climate. The region has resisted the usual tendency to attempt to predict the future, instead embracing resilience as a framework that can help the region create the conditions that will allow it to thrive in the face of a wide range of possible futures.

The strategy outlined five ‘resilience interventions’, or ways to try to influence the resilience of the Goulburn Murray region using targeted foundation activities. These interventions were based on resilience principles and were community-supported.

The interventions will help build the resilience of things that are important to the region, including the ability of the agriculture sector to address challenges; increasing skills and knowledge to boost innovation in the face of change; developing a circular economy; supporting natural and built assets in the region; and fostering leadership and coordination.

An example of a resilience approach that has borne fruit this year is the City of Melbourne Resilience Strategy, adopted in 2016. The strategy had three flagship actions: an urban forest strategy, an emergency management community resilience framework and a metropolitan cycling corridor network. In February 2020, the City declared a climate emergency and pledged to fast track 44km of bike paths in four rather than 10 years. Then Coronavirus hit and fear of catching the virus on public transport meant that the city saw a 270% increase in cycling over a 5 month period.

In his book Finding Resilience: Change and Uncertainty in Nature and Society, Brian Walker of the CSIRO quoted Louis Pasteur: ‘Chance favours the prepared mind.’ For RMCG, resilience is an invaluable tool for thinking about and seeking to better understand a system (person, community, business, industry, region) and preparing it to meet the winds of change. It’s not an idea that we should, or will, throw away any time soon.

A bit more, for those who want to go deeper into the concept of resilience

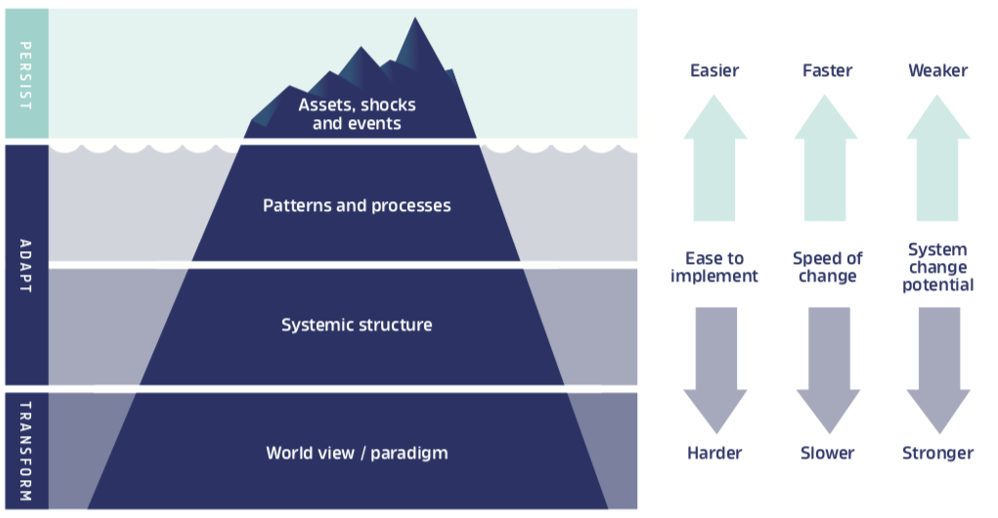

Paul Ryan’s iceberg model of resilience (see Figure 2) shows that efforts to influence a system are most effective when we intervene more deeply within it. As a society, we tend to work above the water line, responding to the shocks and events we can see. When we do that, we fail to address the underlying patterns, processes and systemic structures that can be the true drivers of those shocks and events. Working more deeply in the system may take time and be harder to implement, but adaptation and transformation can result in more effective responses to change.

Figure 2: Iceberg model of systemic change, sourced from the Goulburn Murray Resilience Strategy. Copyright Paul Ryan, the Australian Resilience Centre.

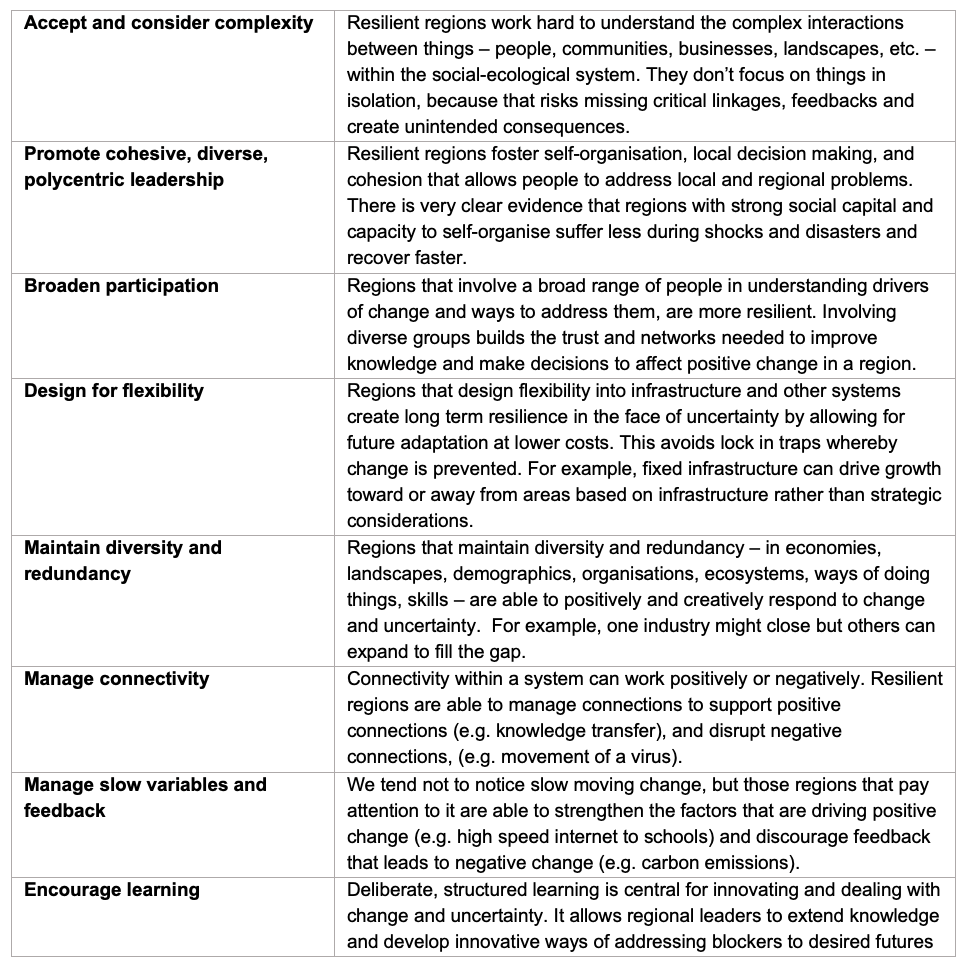

In our work we primarily focus on the resilience of regional communities. Research into system dynamics, particularly resilience theory, tells us that regions that thrive in the face of change have particular characteristics, as summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Characteristics of a resilient region. Principles adapted for the Australian context from principles developed by the Stockholm Resilience Center, Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Schoon, M. (ed) (2015) Principles for Building Resilience, Stockholm Resilience Center.

Get in touch with us

If you would like further information, please contact Claire Flanagan-Smith at clairef@rmcg.com.au or 0427 679 044, or Shayne Annett at shaynea@rmcg.com.au or 0427 679 049.